This is a brief exposé on the importance of paradigm in the methods and conclusions we come to when doing research.

Afrocentricity requires us to locate the researcher in time and space so that we can observe his/her orientation to measure how that affects the outcomes in the research they are presenting to us. In this case, the author (Gábor Takács, PhD) is an Egyptologist/linguist whose orientation is that of “Eur-Asia.” When complicated matters arise when examining ancient Egyptian phenomena, Takács resorts to trying to answer these inquiries by examining the Semitic languages and cultures. In addition, his linguistic methodology is that of “mass-comparison” and I have yet to read a document of his where he applies the comparative method to his linguistic analyses. Below are screenshots of the first two pages of Takács’ article titled “Aaron Ember and the Establishment of Egypto-Semitic Phonological and Lexical Comparison (Part II) (2006).”

The very first entry for analysis is the Egyptian word mnd “breast” (OK, Wb II 92-3), which he equates, after Ember, to Proto-Semitic *mlg “to suck breast; suckle.” Takács goes further and essentially agrees with P. Lacau (1970: 71, #178) in that M-E mnd “breast” should be analyzed as having an m- nomen loci or instrumenti prefix added to an UNATTESTED Old-Egyptian form #wnd “breastfeed.” He claims there is “Afro-Asiatic” support for this term, for an ultimate root of AA *nug-/*lug-, based on the ‘Law of Belova’. Without getting into the details of why this is problematic, this is why it is important when speaking on ancient Egyptian to 1) orient oneself to Africa and look for African answers to obscure Egyptian concepts, and 2) apply the comparative method, both internally and externally, to Egyptian forms.

If Takács would have done this, he’d know that the -d in mnd is not part of the root, but is a suffix of body parts. This -d suffix for the parts of the body can be found in Eg. fn.d/fn.d "nose"; hr.d “child”; ʕȝḏ "becoming pale of face"; pȝḏ "knee, kneecap"; and r.d "foot." The m-n root itself is simply a word for the body and the actions of the body as the following Egyptian lexemes attest: mnḏr "an internal organ" mnḏ.t "cheek; eye" mn.t "thigh"; mn.tj "lap" mnʕ "to nurse; to bring up (a child)" [nipple determinative]; bn.w "a part of the body (waist? buttocks?)"

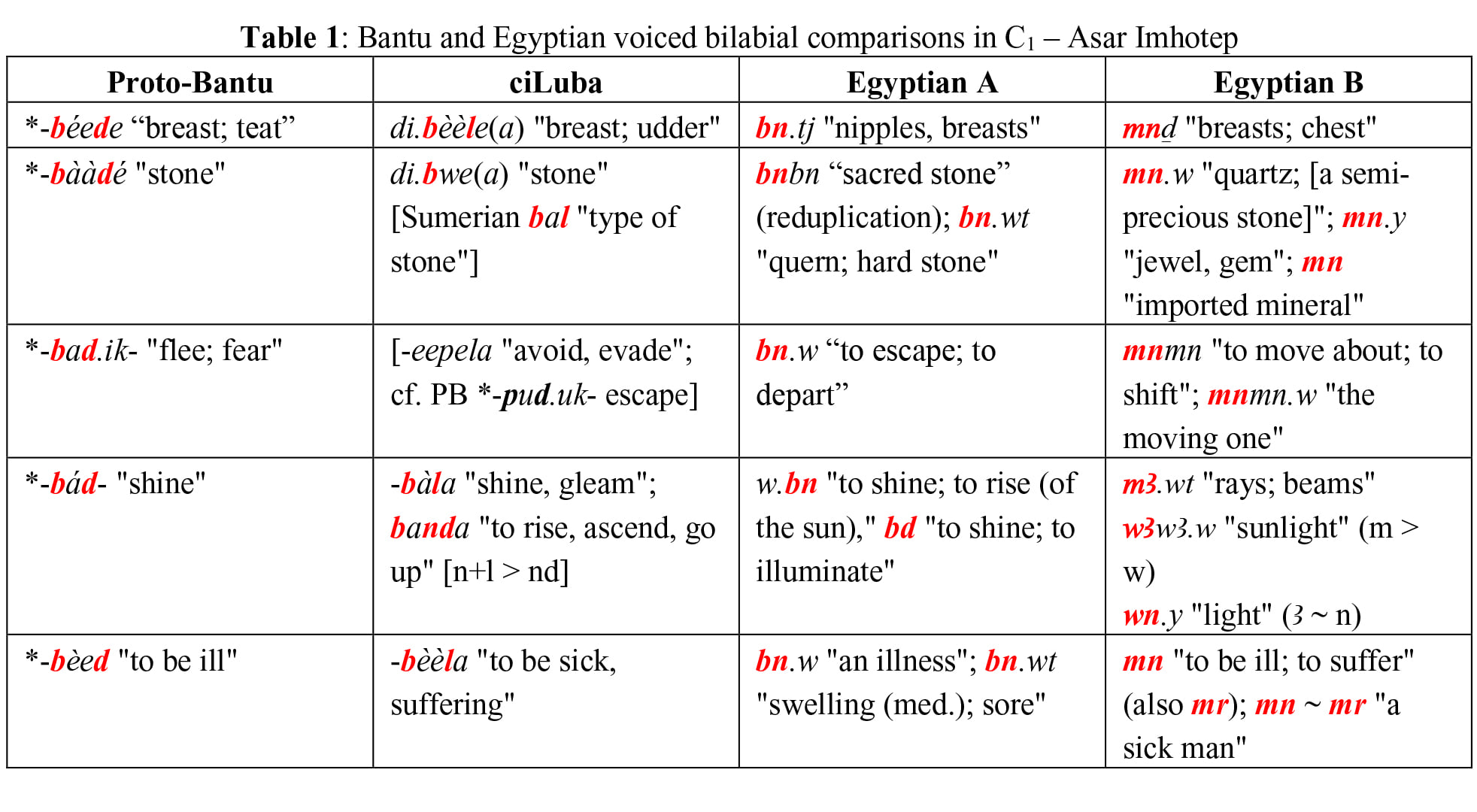

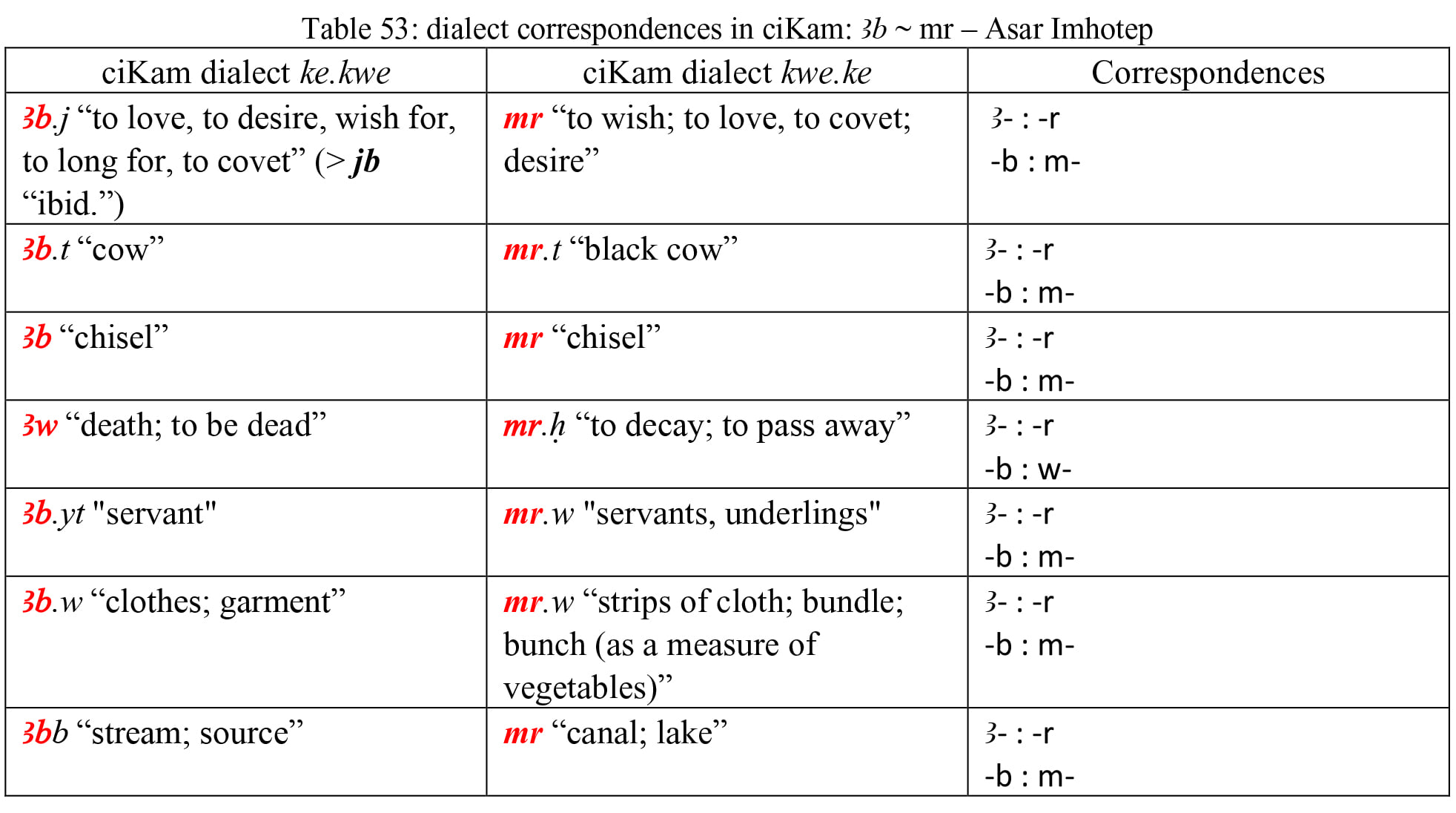

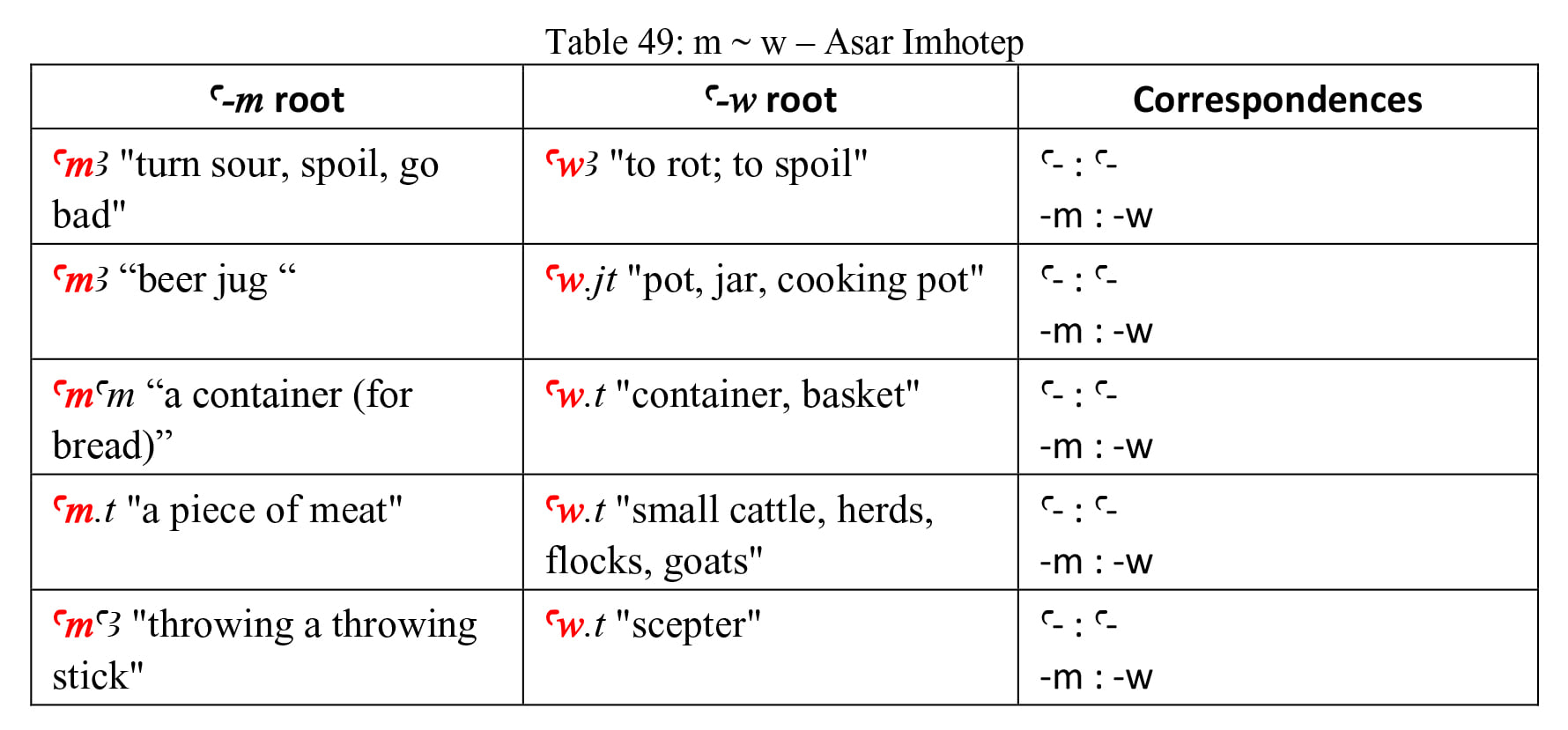

Table 1 above is my comparisons with ciLuba and Proto-Bantu for the Egyptian m-n consonant sequence. I included a series of the Egyptian b-n consonant sequence entries provided my knowledge of Egyptian m ~ b interchanges (Table 53). When I see a series in Egyptian beginning with m-, I automatically search for b- and w- variants (see Table 49 below). In regards to Egyptian mnd “breast,” Mboli (2010) has provided the following correspondences: Sango: mɛ̀̃ "breast"; Zandé: mämu "breast"; Hausa: mā̀ma "breast"; Somali: maal "to milk" (Mboli, 2010: 161).

The suffix of body parts was lost in these languages, but maintained in Bantu in the form of di- (a prefix). This further proves that the root of mnd is m-n and NOT #n-g based on the hypothetical “Afro-Asiatic” correspondences. This is why it is important for us to do our own work, and to show our work (like in mathematics) as not to mislead the reader.

Bibliography

MBOLI, Jean-Claude. (2010). Origine des langues africaines: Essai d’application de la méthode comparative aux langues africaines anciennes et modernes. L’Harmattan. Paris.

Takács G. (2005) “Aaron Ember and the Establishment of Egypto-Semitic Phonological and Lexical Comparison (Part I)”, Acta Orientalia Vilnensia, 6(2), pp. Gabor-Takacs. doi: 10.15388/AOV.2005.0.3968.

Dictionnaire ciLuba

http://www.ciyem.ugent.be/ (French)

Proto-Bantu, BLR3

https://www.africamuseum.be/en/research/discover/human_sciences/culture_society/blr

Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae (see for additional source material cited within the []s)